Engendered Places in Prehistory (1995)

This article was a follow up to the “Households with Faces” article in Engendering Archaeology and the “Men and Women in Prehistoric Architecture” article. This article was written for a new journal of feminist geography. I should say right at the beginning that I consider this to be perhaps the best article I have ever written, but don’t be biased by this statement! I describe the article in detail here since it is very close to my concluding statement in the Opovo monograph (which has yet to be published).

The paper addresses geographers and others who are interested in place and space, who, however enlightened they are when dealing with current contexts of the built environment, tend to be uncreative when dealing with archaeological architecture. They accept unquestioningly the authoritarian word of the archaeologists and their “facts”. Much of the paper is spent in exploring why this is, and how archaeological architecture can be used more creatively in constructing the history of place-making and the continuity of place, the history of the built environment , the history of social action at all scales. I suggest that many of the limitations in the interpretation of archaeological architecture are created not by the data themselves but by the archaeologists and their inability to face the challenge of the ambiguity of the archaeological data. In order to demonstrate how it is theoretical standpoint and not the nature of the data themselves that determine the interpretation of archaeological architecture, I show with examples from the Southeast European Neolithic/Eneolithic period, including excavations that I have directed or participated in (e.g. Opovo, Selevac), how the archaeological record can be “read” differently depending on theoretical viewpoints. The data may be re-interpreted according to a different viewpoint that draws attention to aspects of the record that were overlooked by traditional interpretations, thereby turning into objects of investigation that which had previously been unquestioned, that is, taken for granted. In addition new ways of interpreting the data may lead to a change in excavation methods in which details of the record that were previously ignored as irrelevant are now retrieved from the ground. I show how this happened with my own experience of the archaeological architectural data as my theoretical standpoint changed in the last 20 years. I intersperse in the discussions examples from my own writing (and others) as a self-critique of theoretical viewpoint that is being expressed.

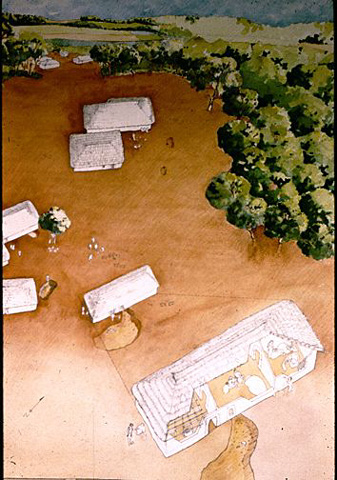

An interest in use-lives of buildings led me to introduce some innovative excavation techniques at Opovo. It also led us far away from traditional aims and assumptions. For example, for us the causes and context of the house-fires became priority objects of investigation. Most of the themes that have been enabled by the broadening of investigative horizons incorporate what we might call multiscalar theorizing within the realm of social relations. The last part of this paper is about the critical awareness of the archaeologist as active mediator limiting and encouraging the reader to view, visualize, imagine, and participate in the interpretation of the built environment of the past. At this point, the focus is on my personal experience in the interpretation of the Opovo data. I describe how my embracing the themes and methodology of post-processualist and feminist archaeology had an effect not so much on the retrieval of data at Opovo, as on their subsequent interpretation. The burned houses at prehistoric Opovo were excavated and analyzed according to the philosophy and values of New (processualist) Archaeology. With my own broadening of horizons of imagination, experience, and question-asking, their interpretation is very different in terms of presentation, the envisaging of the social context, and their meaningfulness. In a feminist interpretation of the archaeological record at Opovo, I have assumed that every aspect of material culture is endowed with some kind of significance for the original occupants, and that we have to be ready to use our imaginations and anthropological experience to envisage what that significance might have been.

In writing the feminist prehistory of this place called Opovo, I interpret the archaeological record in terms of the interweaving of house biographies, the biographies of the imagined actors who lived in the houses, and the social action itself that took place in the houses and outside them. I present an interplay between the different levels of analysis of the archaeological record and different levels of consensus and ambiguity in its interpretation, in which “scientific demonstration” is interwoven with a more interpretive strategy, the use of creative imagination, and alternative forms of textual and visual expression. The problem with this article is to be able to present in linear textual format what such a multiple prehistory looks like. The fulfillment of what this article promises will only be carried out in an entirely different medium – in 1994, the hypermedia Chimera Web, and all of my exporation of digital media of presentation that followed after this article was published.

Abstract

It develops the theme of the feminist and post-processual critique of the processualist and traditional study of archaeological architecture. The article discusses the avenues through which a feminist exploration of archaeological architecture may proceed in practice, using data from Opovo and other sites in Southeast Europe.

Citation

Tringham, Ruth (1994) Engendered Places in Prehistory. Gender, Place, and Culture 1(2):169-203.

Reprinted in: Thomas, Julian (editor) 2000 Interpretive Archaeology. Leicester University Press, London, UK, pages 329-357

Reviews

Mentioned in Brian Fagan (1994) In the Beginning 8th edition, Prentice-Hall, Saddle River NJ. pp.390-392 and later

Mentioned in Julia Hendon (1996) Archaeological Approaches to the Organization of Domestic Labor: Household Practice and Domestic Relations, Annual Reviews of Anthropology, 25:45–61