Experimentation, Ethnoarchaeology and the Leapfrogs in Archaeological Methodology (1978)

This chapter was originally presented in a symposium in the School of American Research Advanced Seminar series held in Santa Fe, New Mexico during November 17-21, 1975. This was an interesting point in my archaeological career. I had been in the US teaching at Harvard University for four years, with research focused on contact or microwear trace experiments on lithic materials including flint and cherts, from various Neolithic sites in Southeast and Central Europe, but I had not yet started my own field project. The project at Selevac (Yugoslavia) would start the year after this conference in 1976. At this point I was more interested in the design of Middle Range Research to provide information in how the stone tools had been used, than I was in the chronology and cultures of European prehistory. My thinking was that the research and ideas that I talk about in this chapter would be appropriate to any place or time which used such materials, no matter what the historical context. From this point of view I was positioned at this time firmly in the framework of Processual Archaeology, but not entirely. I did start a lively discussion about Middle Range Research, critiquing some of Lew Binford’s use of ethnographic observations (that’s where the “Leapfrogs” come in.

Abstract

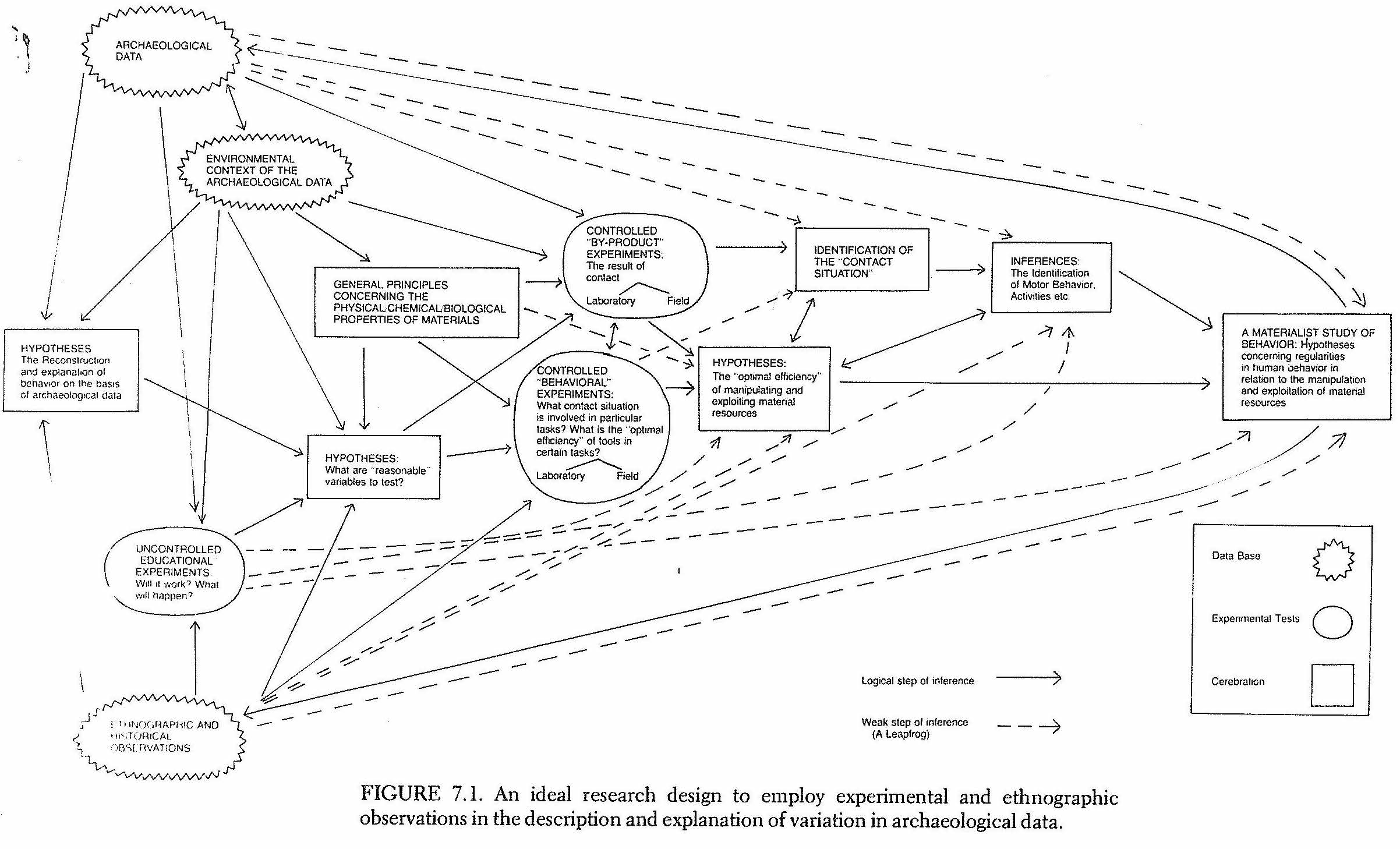

The main thrust of this essay is that observation of and experimentation with archaeological materials cannot be separated from hypothesis building and testing, and, as a corollary, that basic research in archaeological materials is as much an integral part of archaeological question answering as the philosophical model building of Binford, Plog, and Clarke.

The two aspects of archaeological research discussed here – ethnoarchaeological and experimental archaeology – both manifest many of the attributes of traditional empirical investigation and have been spurned and belittled by the philosophers of archaeology as peripheral to the New Methodology, as unscientific, and as having only specific time-space utility. This chapter examines the methodological procedures by which these two aspects of our discipline may be transformed to play an integral part in hypothesis testing and in the formulation of probability statements in archaeological research.

We can define ethnoarchaeology as the structure for a series of observations on behavioral patterns of living societies which are designed to answer archaeologically oriented questions. “Experimental archaeology” – that is, experiments as part of archaeological investigations – on the other hand, comprises a series of observations on behavior that is artificially induced. Both may involve more or less rigorously controlled conditions and recorded results.

Both are important aspects of a materialist study of behavior, pertinent to the study not only of past behavior but also of that of the present and the future. Theoretically, both ethnoarchaeological and experimental observations should provide valuable resources for testing hypotheses concerning archaeological data. Ethnoarchaeological observations are not in competition with experimental observations in providing valuable data on behavior; their information is of a different kind, and this distinction should be made self-consciously when using these data, since it affects conclusions and the confirmation of hypotheses.

The stress in this chapter falls on the side of experiments in archaeology, since my own research has been directly concerned with this aspect of archaeological testing. But my argument will emphasize that both sources of information, although separate, increase their value in interpreting archaeological data when one recognizes and takes advantage of their close interrelationship and interdependence.

Citation

Tringham, Ruth (1978) Experimentation, Ethnoarchaeology and the Leapfrogs in Archaeological Methodology. In Explorations in Ethnoarchaeology, edited by R. Gould, pp. 169-199. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.